Leonardo da Vinci‘s secrets are many. This symbol of the Renaissance Italian art was an all-round artist and illuminated mind. But he liked his mysteries.

We all know he is Mona Lisa’s father, the most enigmatic painting ever created. Also, we know about his uncontrollable genius, creativity, and about his quirky habit of writing from right to left.

Yet, there is so much still to discover, when it comes to Leonardo. From his origins and his spiritual beliefs, to the name – and gender – of his lovers. All the way to the hypotheses proposed in the pages of contemporary best sellers. Indeed, da Vinci continues to be source of interest and curiosity.

Leonardo Da Vinci’s secrets: his mother

Let’s start from the very beginning. Leonardo was born on the 15th of April 1452 in Vinci, a small village near Empoli, in Tuscany. His father was Piero, Florentine notary and notorious womanizer. And his mother was Caterina.

Her figure is shrouded in mystery, because she spent little time with her son. In fact, she sent him to live with his father. So, no one is 100% sure of who she was. Local historians poured their minds and eyes into Vinci’s archives. They managed to come up with a couple of names: some say Caterina di Meo di Lippo, a pauper who lived in a neglected farm near the village. While others Caterina di Antonio di Cambio, the daughter of small landowners.

Oriental origins?

Yes, that’s a plausible theory. How’s that possible, you may ask.

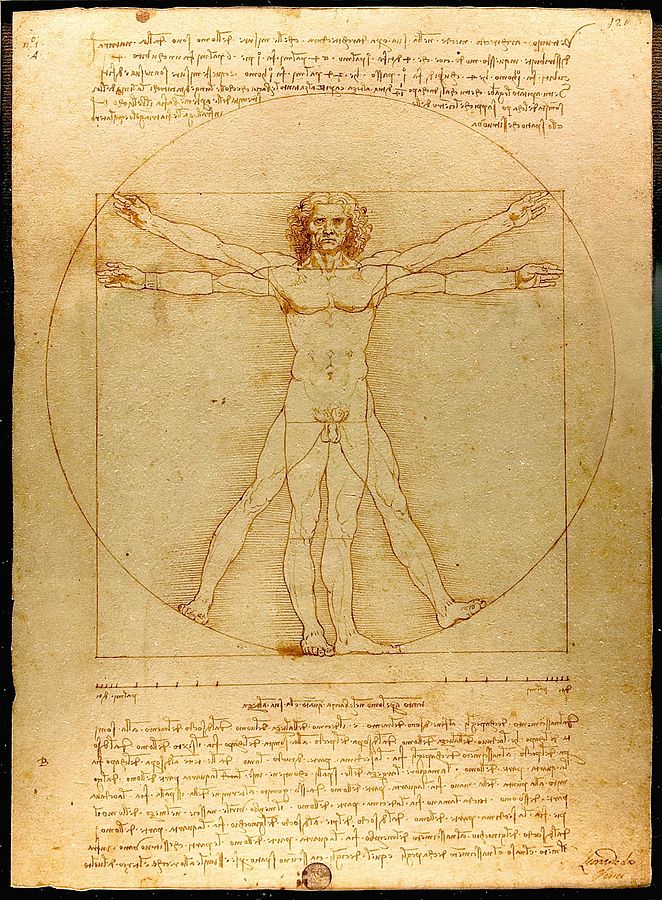

In 2006, a team of researchers from the universities of Chieti and Pescara managed to reconstruct Leonardo’s left index’s fingerprint. And, lo and behold, its structure would be typical of individuals of Arabic descent. Also, Caterina was a common name among women who converted to Catholicism,. Hence, some have speculated Leonardo’s mom could have been a former slave coming from the Middle East.

Nothing conclusive, but more details could emerge this year, after a long awaited DNA test will be carried out by the people of the Leonardo Project. It’s an initiative that brings together experts from Italian, French, Spanish, American and Canadian universities. Their goal is to learn more (through genetics) about the artist’s physical appearance, diet, health and personal habits.

Leonardo Da Vinci’s secret: his love life

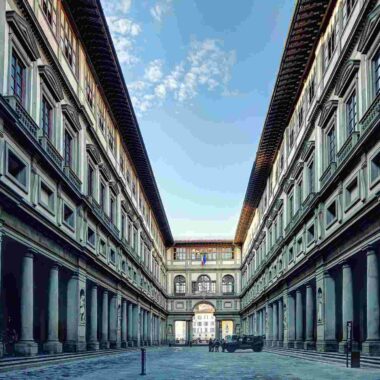

In 1469, thanks to his talent and his father’s connections, Leonardo entered the workshop of Andrea del Verrocchio, the most prestigious in Florence. Very soon, he became his master’s favorite apprentice, to the point some speculated theirs may have been more than a simple mentor-mentee relationship.

In Renaissance Italy, homosexuality was illegal. Even if we don’t have any hard proof about Leonardo’s sexual preference. He may have left some hints, like a plethora of anatomically detailed male members drawings. There’s also a sodomy report filed in 1476 against him, but accusations were dropped because it was anonymous.

Rumor has it

Nothing factual, then, but two names recur often in the discussion. These are Gian Giacomo Caprotti, known as il Salaì, and Francesco Melzi. Both were his students, but for many, they were also his lovers.

Jacomo Caprotti became Leonardo’s apprentice in 1490, when he was only 10. He came from a humble Milanese family and he was a bit of a hell raiser, with a penchant for playing tricks on his mentor and, every now and then, even for stealing some money off him. Caprotti’s mischievousness gained him the nickname of Salaì, Saladin, given to him by Leonardo himself.

As a young man, Salaì was beautiful and ephebic and became subject of many of Leonardo’s sketches, as well as inspiration for some of his works, including the Saint John the Baptist, today at the Louvre. Leonardo indulged him with gifts and kept him by his side even when it became obvious the artistic career wasn’t for him: Salaì was more of a pragmatic type, and helped his master to keep order in his financial and professional affairs.

Things were to change in 1506, when a young Milanese of fine features and noble origins, Francesco Melzi, joined Leonardo’s atelier. Melzi was 15, handsome and cultured, something Salaì, who came from a family of much lower extraction, wasn’t. And so, the interest of Leonardo for his “Saladino” waned, while that for Melzi grew, so much so the young man followed him around even when he left Milan.

Leonardo, however, never forgot Salaì: he brought him with himself and Melzi to Amboise, in France, and left him a conspicuous inheritance in his will.

Leonardo in Literature

That a genius with such talents and life attracted the interests of the world of literature goes without saying, especially when considering that some of Leonardo Da Vinci’s secrets really could make a good book.

Indeed, if you think Dan Brown (more about him in a moment) was the first to pen a Leonardo-centric best seller, you’re mistaken. Up to the end of the 19th century, however, most of the literature dedicated to him reflected an interest in his work and focused largely on his paintings.

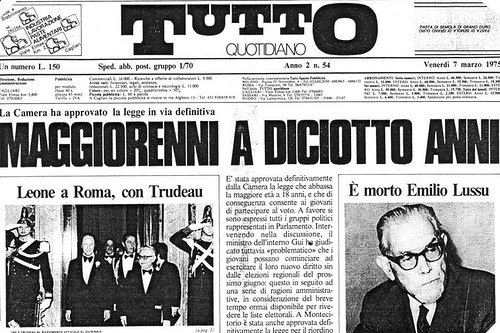

But then, the 20th century came. With it, an interest towards Leonardo that transcended the artistic. In 1910, father of psychoanalysis and man of a thousand controversies Sigmund Freud wrote an essay, Leonardo Da Vinci: a Memory of his Childhood, dedicated to an analysis of the artist’s personality, based on the interpretation of selected paintings. Mario Taddei, historian and director of the Leonardo3 museum in Milan, notes how Freud may have been the first victim of that “interpretive sensationalism” that was to characterized so much Leonardo-related literature in the decades to come. Freud was, for instance, the first to advance the theory about Leonardo’s homosexuality which, in spite of the presence of some evidence, has yet to be proven.

One of the earliest examples of fiction based on Da Vinci was Leonardo’s Judas, by Czech fantasy novelist Leo Perutz, published in 1959, after its author’s death. In it, Perutz describes Leonardo’s relentless search for the right person to become the model for The Last Supper’s Judas. It’s a novel dense with philosophical meaning, already witness to an interest towards the painter far from his value as an artist and inventor.

Bufale Leonardesche

The 1980s brought about a series of peculiar studies about Leonardo, some of them based on notoriously fake sources. The so called Romanoff Codex – which never existed – was at heart of Leonardo’s Kitchen Notes, by Shelagh and Jonathan Routh. The British couple created a curious story about Leonardo being a culinary genius, who worked as a waiter while at Verrocchio’s atelier and, later, even opened a restaurant with – wait for it – Sandro Botticelli. They even went as far as attributing to him kitchen related inventions, such as napkins and pepper grinders.

Nothing of what the couple wrote in their book turned out to be true.

The Biggest Lie of Them All: Dan Brown and the Da Vinci Code

Who isn’t familiar with Dan Brown’s successful esoteric-historical adventures of Professor Robert Langdon? Love him or loath him, the American novelist hit the jackpot when he created Langdon’s saga, especially when The Da Vinci Code was published in 2003. For those who haven’t read it, the novel revolves around the idea that Christ didn’t die on the cross but went on living and married Mary Magdalene. Among their descendants, famous European Medieval rulers, the Merovingians.

According to Brown, a selected few throughout history have been aware of this, and they’ve all been members of the Priory of Sion, of which our Leonardo had been a great master. Because of this, Brown continues, his paintings are filled with symbols recalling the secret his group protected.

Brown skillfully introduced his novel with a note explaining he had based it on historical documents: spoiler alert, that was a lie. Historians were quick to refute Brown’s theory and the author had eventually to admit they were right.

The damage was done, though: because lower-tier literature has more readers than academic journals, a large number of people around the world still believes Leonardo hid secret messages about Christ in his paintings. Just another chapter to add to the multifaceted, incredible story of Leonardo Da Vinci’s secrets.