A variety of grains bolster the Venetian table. Rice and cornmeal are ubiquitous, like the inevitable pasta.

Rice

Venice’s location at the edge of Italy’s largest agricultural plain, drained by a vast river system, has given it rice. In a thousand ways, rice is nearly as essential to the Venetian cuisine as it is to Chinese. The rice that is cultivated throughout the valley of the Po River and its many tributaries in northern Italy is used mostly for risotto, from the piedmont in the west to Friuli in the east. But nowhere is risotto as varied, colorful, and glorified as in Venice.

The Italians have the Arabs to thank for rice. They brought rice to Spain in the 9th or 10th century, and the Spanish introduced it to southern Italy. Then in 1475 the duke of Milan gave the duke of Ferrara twelve sacks of rice to plant. Thence began extensive cultivation in the Republic of Venice and by the next century it was all the rage. Risi e bisi, a soupy risotto is made with the finest young peas to celebrate St. Mark’s Day, April 25th.

Risotto is sometimes tinted with saffron in Venice. Or it may take on the roseate hue of radicchio, a verdant cast from asparagus or a puree of little green lagoon fish called go, or the earthen tones of seasonal wild mushrooms, and frequently it is nearly black from the ink of cuttlefish. Snowy risotto, simply made with butter and Parmesan cheese is commonplace. Every conceivable vegetable, seafood, and meat can go into risotto. There is even a savory risotto made with grapes. The frugal Venetian does not hesitate to stretch a bit of leftover into half a meal by amplifying it with rice.

Regardless of flavorings, the proper results can be achieved only by using the plump, pearly, short to medium grain rice from the Po Valley, the only rice that can be stirred as it cooks without breaking. In Venice risotto is often made with a slightly more liquid consistency than elsewhere in Italy, giving it the surname all’onda, “with waves.”

Arborio is the most common of the finest or superfine, Risotto rices grown in northern Italy, and the one most widely available elsewhere. Two others, carnaroli and vialone nano, are slightly firmer and sought for risotto by the conoscenti. Like most Venetians, Francesco prefers vialone nano, which some shops in America and elsewhere now carry.

Polenta

Porridges called puls or pulmentum had been made from a variety of grains since Roman times, but the Venetians were the first to turn corn from the New World into this staple. In 1861 William Dean Howells, the American consul in Venice, described food shops with “mountains of polenta plates of minnows, bowls of rice, roast poultry, dishes of snails and liver, and vast heaps of frying fish.”

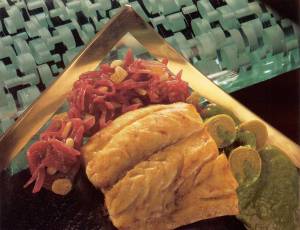

Venetian refinement demanded fine white cornmeal for polenta, and indeed, today white polenta is more common in the city than yellow. Polenta may be the food of the poor, but it takes on an unmistakable elegance in the hands of Venetian cooks.

Outside Venice proper, in the rural, mountainous area of the Veneto, a cauldron-like copper pot of yellow polenta stirred with a long wooden stick offers daily sustenance. Traditionally, the just-cooked steaming mass of cornmeal is turned out on a linen napkin, cut with a length of cotton thread held tight and served at once. Francesco, who grew up in Mestre, Venice’s mainland industrial lifeline, recalls huge platters of polenta enhanced by a sausage or two for dinner. Polenta e oseletti scapai refers to polenta with the “birds that got away,” in other words, served with sausage or mushrooms perhaps, when the hunter came home empty handed.

Any cornmeal can be used for polenta – an import is unnecessary – but stone-ground cornmeal is best. White cornmeal tends to be finer; yellow usually has a coarser texture. It is simple to make and leftovers never go to waste.

Freshly made creamy polenta can be used as lushly comforting as mashed potatoes. In Venice and elsewhere, it is also permitted to cool thoroughly and transformed on the grill or in the sauté pan into a crisp, gilded cake. Grilled or fried polenta cut into squares can replace bread for an hors d’oeuvre, becoming the underpinning for sautéed mushrooms, or complement the strong flavors of country cheese, creamy baccala (salt cod), or spicy cuttlefish in ink.

See polenta recipes.

Pasta

Marco Polo may be the apocryphal father of Italian pasta, but in Venice, where risotto and polenta star, pasta is often of secondary importance. As in other regions of Italy, the type of pasta used in a dish, dry, store-bought or freshly made egg pasta is a function of flavors and ingredients.

Dry pasta, usually spaghetti, is the type used for most seafood. One exception is ravioli, which is often served with seafood fillings in Venice. Spaghetti is paired with reddish beans for a classic soup, pasta e fagioli, or in the soft sibilant dialect of Venice, “pasta e fasioi.”

In this region a kind of thick spaghetti called bigoli is made from whole wheat (wholemeal) and served with simple but richly flavored mixtures of anchovies or shreds of duck or game. Gnocchi, the tender little dumplings made of mashed potato and sometimes pumpkin, are another Venetian favorite, also popular in the mountainous area to the north that segues into the Tyrol.

See Pasta repices.

By Francesco Antonucci of Remi Restaurant New York City-