In occasion of International Holocaust Remembrance Day on the 27th of January, anniversary of the Liberation of Auschwitz, we decided to dedicate an article to the history of the Italian Jewish community during the “Ventennio,” before and after the promulgation, in 1938, of the Leggi Razziali, Mussolini’s racial laws against the Italian Jews.

Even though the magnitude of this specific aspect of the Second World War was not as abominable as in other parts of Europe, the amount of Italians of Jewish faith who lost their lives during the Shoah amounts at around 7.800, over a number of about 8.500 deported. Most of them lost their lives in Auschwitz.

One of them, Primo Levi, came back to tell his harrowing story in three beautiful, haunting works: Se Questo è un Uomo (If This is a Man), La Tregua (The Truce) and I Sommersi e i Salvati (The Drowned and the Saved). A survivor of the Holocaust he, however, could not survive the pain and horror of what he experienced and committed suicide in 1987, 42 years after having left Auschwitz as a free man.

The Italian Jewish Community before the 1938 Racial Laws

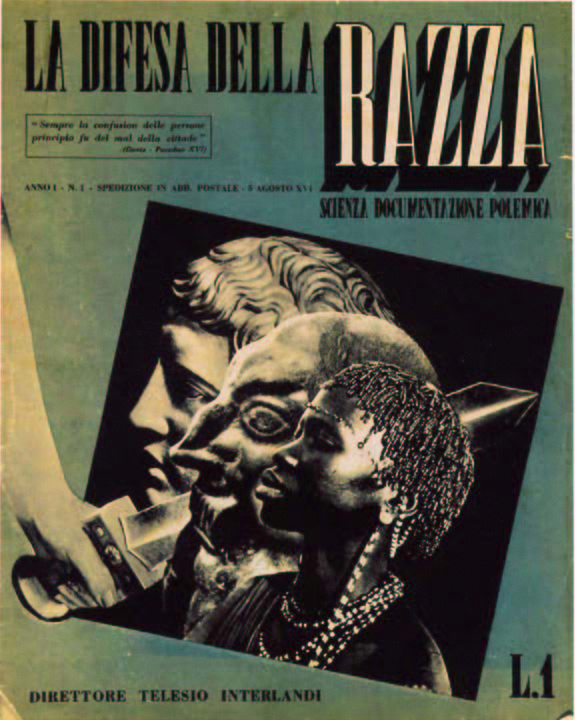

publication (8th of August, 1938) (wikimedia)

Between the end of the 19th and the beginning of the 20th century, the Italian Jewish community was not large: in 1938, it reached 45.000.

Italian Jews had been, however, often central to the history of the country, especially during the Risorgimento and after the Unification of Italy. They were involved in politics (Italian Prime Minister Sidney Sonnino was of Jewish faith). Italian Jews were socially and culturally integrated, to the point there was no difference in habits, language and mores to the rest of the Italians.

To say it very simply, Italian Jews felt first and foremost Italian: beside their role in the creation of Italy during the years of Risorgimento, they contributed to the Italian war effort during the First World Conflict (the Italian army had 50 Jewish generals) and many adhered to Fascism with convinction.

Their natural and complete socio-cultural integration had historical roots: when Italy became a kingdom in 1861, Jews became full Italian citizens, a characteristic they did not have in other states. Italy, moreover, did not have a strong history of anti-semitism – albeit some historians have recently debated this specific point – even though there had been segregation during the Middle Ages and the Renaissance.

The Jews of Italy, then, were part of society just as any other Italian and belonged to every social group: there were intellectuals, politicians (also within Mussolini’s Fascist party), workers, farmers. Poor and rich: the idea that all Jews were highborn and wealthy did not mirror reality in Italy.

Many of them were registered – and at times very much convinced – members of the Fascist Party: in 1938, when the Racial Laws were emitted, they were 8.906, about 30% of the whole community.

The Racial Laws and the War

“The population of Italy is of Aryan origins and its civilization is Aryan. There now exists

a pure Italian race and the Jews do not belong to that Italian race…”

From the text of the Fascist Racial Laws

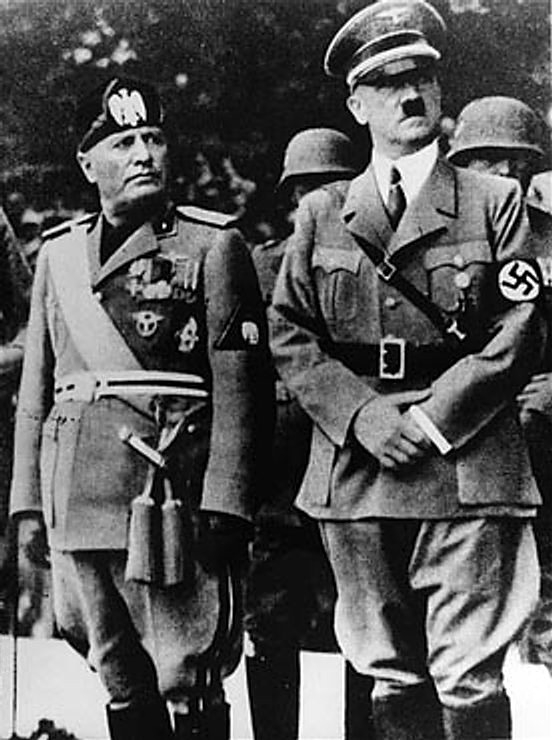

The reasons behind Mussolini’s decision to introduce anti-semitic legislation are to be sought in his alliance with Nazi Germany. Even though Fascism did believe in the cultural and historical superiority of Italy, particularly in name of the greatness of the Roman Empire, it did not have racially discriminating undertones. Even one of Mussolini’s most notorious lovers, writer and art critic Margherita Sarfatti, had Jewish roots, and nobody found it astonishing.

Racial Laws (wikimedia)

However, when Hitler’s influence over his ally strengthened, Mussolini decide to embrace Nazi’s anti-semitic policies.

Introduction to the Leggi Razziali, promulgated towards the end of 1938, was Italy’s Manifesto Razziale (Racial Manifesto), conceived, written and signed by a number of well-known and relevant scientists and academics of the time. In it, a newly discovered racist sentiment was disclosed to the country: in 10 points, it described to the people of Italy that races, which were biologically based, existed and that there were some superior to others. The Italian race was pure and aryan and, as such, had right to rule above others.

The anti-semitic legislation of Italy had a clearly biological connotation and hit the Jewish communities the hardest: all people related to “the Jewish race” were persecuted, regardless to their religious faith. According the the race census carried out in August 1938, 51.100 people were affected by the laws, 46.656 of which were Jewish.

Among other things, the Laws:

- forbid marriage between non-Jewish and Jewish citizens

- forbid all national offices, as well as private firms operating in the public sector, to have Jewish employees

- revoked Italian citizenship to all foreign Jews who entered the country after 1919

- forbid Jewish children to attend Italian national schools, and imposed the creation of Jewish schools

- severely reduced the possibilty for people of Jewish descent to work in schools and universities

- did not allow Jewish people to serve in the military

- did not allow Jewish people to be legal guardians of minors

- did not allow Jewish people to own firms producing anything that was needed in the defense of the country

“Aryanized” Jews, that is, those who accepted to be baptised and change faith, were allowed to serve in the military, be guardians of minors and supply Italy’s defense forces with material.

Mussolini envisaged a policy of emigration and expulsion for the Jews of Italy, but this was not simple to achieve because of the community’s thourough social integration, where mixed marriages and families, along with full professional and cultural assimilation had been making it difficult to carry on with the expulsion process. Many decided to emigrate nonetheless: between 1938 and 1941, when the frontiers were closed because of the war, about 8% of Italian jews had left the country.

In the month of June 1942, Mussolini employed a few thousand Italian Jews for forced labour and, the following year, began preparing a plan to imprison as many Jews as possible in four labour camps: he never managed to do it, because his government fell on the 25th of July 1943, before he could carry out his plan.

However, the real tragedy for the Italian Jewish community still had to start.

With the fall of Mussolini, Nazi forces began deportations to their extermination camps in Italy, too. It is between 1943 and 1945 that the Italian Shoah took place.

As mentioned, about 8.500 people were deported in two years, 7.800 of whom perished. A small tall numerically, when compared to the enormous numbers of Germany and Poland, yet a sad contribution to one of history’s most horrific tragedies.

Words of Remembrance

The Shoah has been recounted and remembered by those who survived it in literary pieces of, at times, touchingly painful beauty. If you are interested in reading about the experiences of Italians in those years of pain, Primo Levi autobiographical works on his own experience in Auschwitz are an excellent place to start. True world literature classics, you will be haunted by his words for days after closing for the last time the back cover of any of the works below. The Drowned and the Saved, which I got to know as part of the syllabus for an Italian literature exam in university, is one of my favorite books, but one I did not have the strenght to open again for years after I had read it for the first time: bleak, real, painful, unsettling, it should be compulsory reading in every school in the world.

During his lifetime, Primo Levi published three works about his experience in Auschwitz and its aftermath: If this is a Man (titled Survival in Auschwitz on the American market), about his permanence in the extermination camp, The Truce, about his trip back to Italy after his liberation and the already mentioned The Drowned and the Saved, a chilling essay on the guilt experienced by survivors and the senseless evil that caused the tragedy of the Shoah.

After his death, other texts were published, among them The Black Hole of Auschwitz and Auschwitz Report. Levi was blessed with a fine narrative voice that made his works classics of modern Italian literature.

Francesca Bezzone