I don’t know about you, but I love history and I find it all interesting: from military history to biography, from ancient Rome to the Second World War, I can read up history books as easily as I eat cake (and I eat a lot of cake, believe me). I also happen to be a historian by education and I spent most of my adult life reading and researching about history (Late Antique, to be precise).

I adore history, so, but I am aware not everyone feels the same way about the past, especially if the only contact with the subject came from those tedious, musty books we all had to study in high school. This is when curious facts or little known events come handy: they spice up things a bit and make it easier to develop a passion for this fascinating discipline. Italy has a very long history and, as a consequence, plenty of curious and little known facts about its people. Let’s take a look at some!

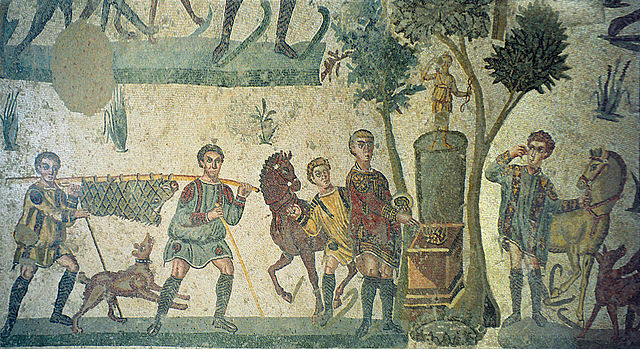

Roman Soldiers and Tattoos

(at least during the later years of the Empire) (Allyde Winters/flickr)

Historians and history – and tattoos – lovers alike have been discussing about this for decades and, in truth, the topic is still very much debated. At the same time, we can state with relative ease today that, at least during the later Empire, Roman soldiers did bear tattoos on their body.

However, forget about decorative tattooing as we know it today. The practice of branding and tattooing was known by the Romans, as it had been practiced by people they came into contact with or conquered, yet, it was not considered highly. It was mostly criminals and slaves who got tattooed during the Empire. Things began to change, however, when soldiers got into the habit to have the SPQR acronym (Senatus Popolusque Romanus), or an eagle (symbol of the Roman army) tattooed on them, to show they belonged to the army. During the late Empire military tattooing became apparently more common and ended up substituting the signaculum, the equivalent of today’s soldiers’ ID tags. It seems the practice came into being to discourage desertion.

Vegentius, in its “Epitome of Military Science” does mention the practice: he lived during the 4th century AD, which seems to strenghten the idea military tattooing became more common in the later years of the Empire. Supporter of the theory is Lindsay Allason-Jones, director of CIAS (Centre for Interdisciplinary Artefact Studies) and reader in Roman Material Culture at the University of Newcastle, UK.

Read more about it: C.P. Jones, “Stigma: tattooing and branding in Graeco-Roman Antiquity” (in The Journal of Roman Studies 77, 1987).

Pompeii and the real date of the Vesuvius eruption

Let’s move from Rome to one of its Empire’s best know cities, Pompeii. Before being obliterated from the face of earth, Pompeii was a thriving commercial hub and home to some of the richest people in the Roman world.

Or so we have all learnt in school.

In truth, things were a bit different for Pompeii and its people in the 1st century AD, and it was all fault of the Vesuvius. About 17 years before its end, Pompeii had suffered an enormous earthquake, which had profoundly damaged the city, architecturally and economically: many of the wealthier families had left after the disaster, and not all of their villas had been fully restored when the eruption took place. In 79 AD, Pompeii was still a rich town, but only a shadow of what it used to be and signs of it are still visible on what archaeologists unhearted throughout the centuries: construction material was found in many areas of the city and a number of buildings were destroyed when still under construction. All this points to the fact the city was still in the midst of being reconstructed after that tragic, earlier earthquake.

Many of us may have wondered if the people of Pompeii were aware of the incumbent danger: truth is, they weren’t. Pompeians didn’t know they lived by a volcano, as the Vesuvius, at that time, didn’t look like one. It was shaped more like a mountain with a low, flat top, which was intensively cultivated in name of the fertility of its soil. It was, in fact, the Vesuvian eruption of 79 AD to give the volcano its current shape.

There’s more: tradition and history both have always placed the fatal eruption during the Summer, but archaeological evidence seems to prove that, in fact, it happened later in the year, very likely between the end of September and October. The presence of high quantities of wine amphorae shows that grapes had been already harvested and wine produced. This would pinpoint the time of the eruption in the Fall, rather than the Summer. Moreover, archaeologists have unhearthed large numbers of carbonized fruits such as figs, which ripen during the Fall, and seeds typical of autumnal herbs and plants.

Read more about it in: “Pompeii, the Living City” by Alex Butterworth and Ray Laurence; if you feel comfortable reading in Italian, then look no further than Alberto Angela’s “I Tre Giorni di Pompei, ” an easy to read, yet historically accurate account of Pompeii’s last hours.

Libertine convents

Convents are considered places of faith, rectitude and meditation, but in the 18th century it wasn’t quite so. This was particularly true in Italy and especially in Venice. How do we know? Well, chiefly from the memoires of one of the world’s most notorious lovers, Giacomo Casanova. Casanova counted a fair share of nuns and abesses among his lovers, some of them so well introduced to the art of love to make him blush. Especially famous were his romps with the notorious M.M., later indentified as Maria Morosini, a nun of illustrious origins, whom he shared with soon-to-be cardinal François-Joaquim de Pierre de Bernis. Lord Byron, who lived in Venice for a long time, was known in the city for his talents under the sheets and was said to enjoy the company of young nuns, too.

Literature brings more examples of claustral debauchery in I Promessi Sposi (The Bethroted), with the figure of the lascivious “monaca di Monza,” and in Giovanni Verga’s Storia di una Capinera (History of a Capinera) centered on the life of Maria, a young woman forced to enter a convent by her family. She falls desperately in love with Nino and such love will eventually lead her to madness and death.

In fact, Maria’s own situation was common to many girls and boys of the time, and can be considered the origin of the “libertine convents” phenomenon. It wasn’t unusual to force a family’s youngest child to religious life: by doing so, families freed themselves from the duty of supporting them financially and, in case of girls, didn’t have to worry about their dowry. This meant many nuns and priests were, quite simply, not cut for it and kept on living as if they weren’t men and women of God.

Read more about it: ” The Story of my Life,” by Giacomo Casanova.

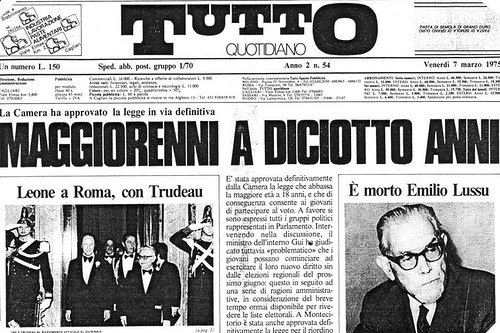

The first King of Italy Spoke very little Italian

(André Adolphe Eugène Disderi/wikimedia)

When we think of the unification of Italy, we think of three names: Giuseppe Garibaldi, the military mind; Camillo Benso count of Cavour, the political genius and, of course, Vittorio Emanuele II di Savoia, the first king of Italy.

Vittorio Emanuele was already a king: the Regno di Sardegna was one of the strongest political and military entities in the peninsula and extended its power over a large chunk of northern Italy and western France, as well as the islands of Corsica and Sardegna. To Italians, Vittorio Emanuele is a symbol of the unification of the country as much as Garibaldi is, and he’s considered a true father of Italy and “italianità.” Truth is, however, the king may have had problems communicating with its people, unless they were Piedmontese or knew well French. Yes, because the main language of the Kingdom of Sardegna was not Italian, but French, which was also considered the language of diplomacy: that was the language he knew best.

As a Piedmontese, he also spoke well his dialect, which was the most used form of communication among people: commoners would mostly speak in dialect and would certainly not know Italian. In fact, don’t be surprised if you hear around that Italy was linguistically unified only after the advent of radio and tv, because it’s true. Up to the first half of the 20th century, the majority of Italians, especially those living in the countryside and of lower education, didn’t know Italian much, and would almost exclusively speak in dialect.

Read more about it in: “The Italian Risorgimento,” by M. Clark; “A Coincise History of Italy,” by Christopher Duggan; “Victor Emmanuel II,” by C.S. Foster.

Dante barely knew his Beatrice

(husky/wikimedia)

Dante Alighieri is one of the symbols of Italy’s greatness in art and literature. His masterpiece, La Divina Commedia, is universally known as one of the heights of Man’s literary achievements. Even if you never read it (it’s, indeed, a pretty long affair), you may be familiar with the figure of Beatrice, Dante’s own guide to the ethereal world of Paradise. Her presence in the Divine Comedy is not casual of course, as Beatrice is a seminal figure for the evolution of Dante’s narrative and creative process. In fact, the Divine Comedy isn’t the first place where Beatrice appears: Dante did dedicate to her a beautiful work, La Vita Nova (The New Life) a prose and poetry piece centered on the poet’s love for Beatrice and their story. Beatrice became the epitome of love and the embodyment of the “donna angelo,” the angel-woman, typical of the Dolce Stil Novo, the literary style embraced by Dante.

But who was she and what was her real relationship with the poet?

Well, we know she did exist and her name was, very likely, Beatrice Portinari. She came from a noble florentine family and it’s Giovanni Boccaccio himself, in his commentary to the Divine Comedy, to name her as Dante’s “Beatrice.” Albeit not unanimous, the belief Portinari is the historical person behind Dante’s literary Beatrice is today quite radicated also among historians and literary critics.

What was their relationship, so? Did they really love each other? Did they indulge in illicit love, as they were both married to other people? Well… no and no.

Truth is that, very likely, Dante’s passion for Beatrice remained largely spiritual and platonic and the two barely ever spoke to each other. Probably, Beatrice didn’t even know Dante fancied her so much nor that he had been writing about her, as she died the year he wrote La Vita Nova (1290), which was then published a couple of years later. This text gives us details about Dante and Beatrice’s meetings and let’s just say that, to modern standards, there was very little to write about: they met three times, once when children, another when they were both 18 and a third time in dream. The two barely spoke to each other and their dialogues were limited to formal salutation.

If this gave inspiration to Dante’s incomparable poetry, what would he have produced if his love actually developed into a real relationship?!

Read more about it in: “Vita Nuova,” by Dante Alighieri; “Paradiso” (Divine Comedy’s third section), by Dante Alighieri; “The Figure of Beatrice: a Study in Dante,” by Charles Williams.

If you enjoyed these curious historical facts about Italy, make sure to check out the second part of our selection, More Curious fact about Italian History, where we’ll find out about, among other things, Italy and its ties with Ancient Egypt, the origins of the first modern gynecologist and Fascist Italy and its need for gold.

What excellent and interesting historical revelation!