How did I come out with the idea of writing about Italy’s food of the past? You all know I like the past, so it should come as no surprise that, among my weekly newsagent’s buys there are magazines about history, rather than the most recent issue of Cosmo. When I bought the latest number of a popular history monthly last week, I came across an article that tickled my curiosity and sent me on an online quest to learn more about it.

The topic? The strangest things ever eaten on the peninsula throughout the centuries.

Medieval people roasting meat, from an original 15th century illustration (wikimedia)

Medieval people roasting meat, from an original 15th century illustration (wikimedia)Ok, you may say, lifeinitaly already dedicated an article to Italy’s s weirdest dishes and, indeed, most of them have origins well rooted into the country’s history and tradition. Here, though, we go even further back in time and things, believe me, get even weirder.

From Rome’s notorious garum, a sauce made with rotten fish, to the peculiar Renaissance practice to skin peacocks with their feathers still on, roast them and “dress” them in their own skin again, here come some of the most curious, bizarre and eccentric dishes Italian history handed down to modernity.

Garum: the sauce no Roman would dine without

A garum factory in Baelo Claudia, Andalusia (Andre Skibinski/Flickr)

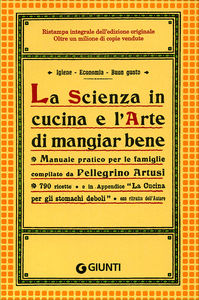

A garum factory in Baelo Claudia, Andalusia (Andre Skibinski/Flickr)If you took Classics in college, you probably are already familiar with garum: the Romans were mad about it, so much so its recipe made it into the most famous culinary work of classical times, Apicius’ De Re Coquinaria. In case you fancied organising a lucullian Roman Empire-inspired dinner, here is how to make it: gut some fish out, put all their innards in a container and let them all rot under the sun, until they liquefy. Then stir and mix them a few times, strain and voilà, your garum is served. To add an authentic note to the whole thing, keep it in an amphora, just like the Romans did.

That is the easy version of the recipe, told with a tad of humor, but garum was in fact a complex ingredient: its taste could change depending on which organs of the fish were used and its production was among the most lucrative businesses in Roman times, bringing prosperity to many a coastal region of the Empire. Pompeii was known for its garum, but the best, according to the literature, came from Spain, Cartagena and Gades producing the most sought after varieties.

Want to try it? It is said famous (and delicious) colata di alici is a cousin of garum, even though the closest modern fish sauce to our ancient Roman prelibacy is south eastern Asian nuoc mam: its preparation is virtually identical to that of garum, especially that of the filipino variety.

Eating a peacock as if it were alive

fThe Italian Renaissance was a time of cultural and artistic enlightment. Provided you stayed out of the kitchen. Or just politely refused any dinner invitation.

Italians of the Renaissance had a penchant for flamboyant dinner parties, but instead of getting an opera singer breaking glasses with an acuto, they served roasted peacocks covered in their own – poached – skin and with their heads still on. Apparently, peacock was common enough on the tables of the European rich and famous before it was surpassed in popularity by turkey, imported from the Americas in the 16th century. Peacocks were beautiful birds, so much so it was a pity to miss on all that beauty when eating them.

So the ingenious chefs of 15th century Italy found a way to maintain roasted peacocks as delightful to the eye as they were to the stomach: they were to be skinned with the uttermost gentleness up to the neck, the skin then left attached to it and pulled over the peacock’s head, which was then wrapped into a damp cloth and spit roasted. The cloth was used to protect the head and the skin from the heat, so they could keep a more lifelike appearance.

Once the bird was perfectly cooked, the skin – complete with feathers, mind – was pulled back upon it. A thin iron rod was inserted through the body of the peacock and up to its neck, so that it would stand straight as if alive.

To complete the picture, a piece of camphor wrapped in brandy-soaked cotton, stuck in the peacock’s beak: once set on fire, the bird turned into a flame-breathing portent.

Did it taste good? Apparently so.

Want to try it? After a careful search, I can safely confirm peacock is no longer a popular choice to impress your guests. Some recipes pop up here and there, but they are usually historical vestiges of Medieval and Roman times.

Those Romans again: roasted dormouse

The last time I saw a dormouse it was on my doorstep, my cat sitting beside it, delighted because he had caught dinner. If we were in ancient Rome, I may have embraced his culinary suggestion without batting an eyelid.

Dormice were consumed commonly by our ancestors, who took such a delight in the tenderness of these little rodents’ flesh they actually bred them: they were kept captive inside large jars called gliraria and fed honey, walnuts, chestnusts and hazelnuts. The little animals grew fat and tender, just as the Romans liked them: they were then cooked according to taste. One of Rome’s best loved recipes – found again in Apicius’ masterpiece De Re Coquinaria – was that of dormouse stuffed with pork meatballs, flavored with pepper and a spice called laser, made from silphium, a plant once common on the coasts of Northern Africa.

A little note about silphium: its extinction, which happened already in Antiquity, is a bit of botanical cold case. The real reason for its disappearance is not clear, even though many reasonable suggestions have been made throughout the centuries. One involves the diffusion of intensive farming in the area, which would have caused a rise in the number of animals feeding on it. Another refers to the possible changes in north-African climate throughout the centuries, which may have transformed a once friendly environment for silphium into a bad one. Last but not least, the slightly conspirational theory of an intensive and uncontrolled colture of silphium itself, which would have transformed the soil’s chemical balance to the point of no longer allowing wild silphium to grow.

The jury on this is, alas, still out.

Want to try it? Apparently, dormouse was still eaten in certain areas of Italy until relatively recently. Brianza, in Lombardia, had roasted dormouse among its traditional dishes, so much so that recipes for it were still presented in local cookbooks as far as the 1970s. Considering the type of animal, I guess eating dormouse may be similar to eating squirrels, which I hear is somehow a thing in certain areas of the US…

Read on

If you have taste for culinary archaeology, here are some interesting reads for you.

On Medieval cooking:

- Odile Redon, Françoise Sabban and Silvano Serventi (2000). The Medieval Kitchen: Recipes from France and Italy.

- Massimo Montanari, Beth Archer Brombert (2015). Medieval Tastes: Food, Cooking and the Table (Arts and Traditions of the Table: Perspective on Culinary History).

On the delicacies presented on ancient Rome’s tables:

- Apicius, Joseph Dommers Vehling, ed. (1977). Cooking and Dining in Imperial Rome.

- Apicius, Elisabeth Rosembaum and Barbara Flower (2012). The Roman Cookery Book: a Critical Translation of the Art of Cooking for USe in the Study and in the Kitchen.

- Ilaria Gozzini Giacosa (1994). A Taste of Ancient Rome.

On the Renaissance and its variety of flamboyant dishes:

- Dave Dewitt (2006). Da Vinci’s Kitchen: a Secret History of Italian Cuisine.

- Bartolomeo Scappi, Terence Scully (2011). The Opera of Bartolomeo Scappi (1570): l’Arte et Prudenza d’un Maestro Cuoco (The Art and Craft of a Master Cook).

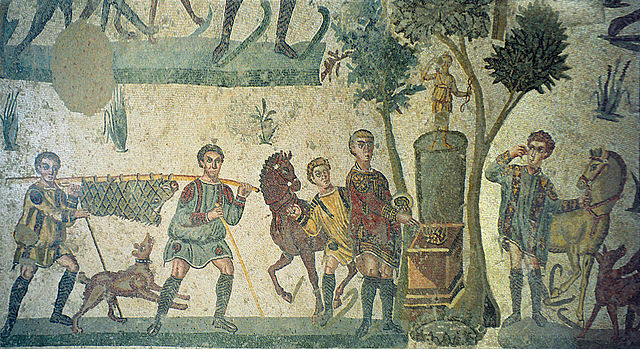

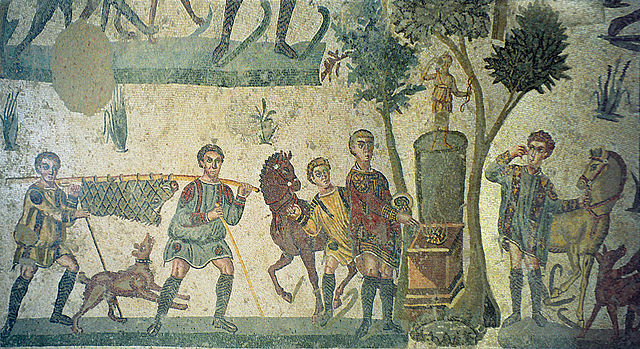

Romans preparing a banquet, in a mosaic in the Villa del Casale, in Sicily (Jerzi Strzelecki/wikimedia)

Romans preparing a banquet, in a mosaic in the Villa del Casale, in Sicily (Jerzi Strzelecki/wikimedia)Inspiration for this delightful piece was taken from Alessandro Marzo Magno‘s piece “Interiora, Pidocchi, Cicale: Buon Appetito!” on the March 2016 issue of Focus Storia.

Francesca Bezzone