In the first part of this article, we presented five curious and little known facts about the history of Italy and its people: from ancient Rome and its soldiers, to the tragic end of Pompeii, up to the times of the unification of Italy, we’ve discovered a bunch of interesting things on this country we all love.

But I had so much fun preparing the first part of this article – and there’s so much curious history out there! – that putting together a second became paramount. Here’re, so, more little known historical facts about Il Bel Paese…

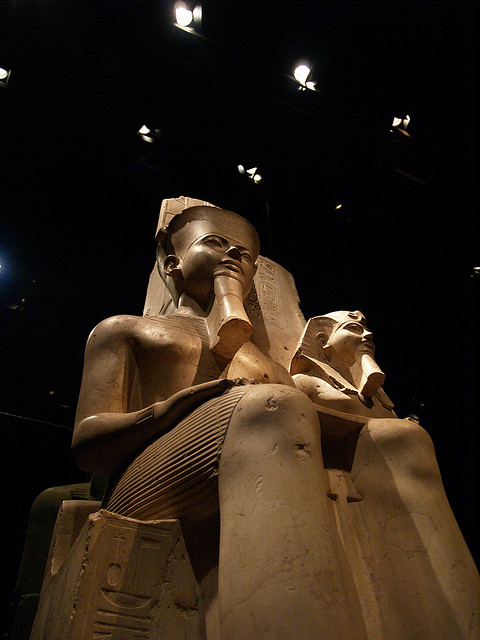

Italy is the cradle of Egyptology

of Turin (Maurizio Zanetti/flickr)

“The Road to Memphis and Thebes passes through Turin”

Jean-François Champollion, father of Egyptology and first man to understand and translate hieroglyphics.

Ancient Egypt is one of my historical obsessions: I’m fascinated by its history in all its facets and I’ve been toying, in recent months, with the idea of learning how to read and write hieroglyphic (but this is another story). In truth, I’ve always been fascinated by it, also because I got close and familiar with mummies and pharaohs very early in life and for real: when I was in third grade, I visited the Museo delle Antichità Egizie di Torino, one of the most popular cultural institution in the city and in the whole of Italy. It was a school trip and one of the first things our teacher told us was that the Museo Egizio di Torino, as it’s commonly known, is the most important of all Egyptian Museums in the world second only, of course, to that in Cairo.

And it’s true.

There’re amazingly rich museums fully, or in part, dedicated to ancient Egypt around the world: the British Museum, the Ägyptisches Museum in Berlin or the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston all have larger collections than the Museo Egizio di Torino, but none matches it when it comes to the quality and relevance –historical and artistic– of its content.

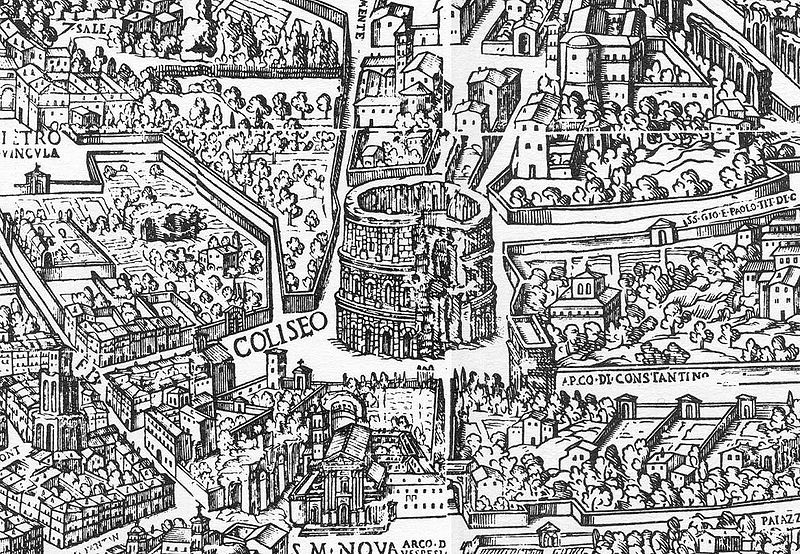

I know it may all sound strange: Egypt and its history became hugely popular at the beginning of the 19th century, after the Napoleonic campaigns in the land of the Pharaohs. As a consequence, it was only natural that egyptology as a discipline was born in France. It was the French, along with the British and the Germans, who lead excavations in the 19th and early 20th century, that is, when most major archaeological discoveries were made.

But you know what? Italians were there, even before Napoleon set eyes on the Pyramids at Giza and Egypt became a trend in the Western world. In 1759, Vitaliano Donati, a passionate archaeologist and historian from Padua, travelled to Egypt and led his own expedition: all that was found, was sent to Turin. When Egypt-mania hit Europe, great Italian archaeologists joined various expeditions, especially French: Bernardino Drovetti was one of them. He eventually sold his own collection to the king of the Kingdom of Sardinia, Carlo Felice, in 1824: Carlo Felice decided to put together Drovetti’s material with other Egyptian collections the Savoias owned and voilà! the first Egyptian museum in the world was born. The greatness of the Museo delle Antichità Egizie di Torino, however, is tied indissolubly with the figure of egyptologist Ernesto Schiapparelli. While director of the Museum, Schiapparelli acquired a large number of relevant finds, and also lead several archaeological expeditions in Egypt to increase the Museum’s collection. It’s, ultimately, thanks to Schiapparelli, that the Egyptian Museum of Turin is today so incredibly important.

The Museum is located in the very heart of beautiful Turin, in the Palazzo delle Scienze, and has been recently entirely renovated.

Learn more about it: “Egyptology: an Introduction to the History, Art, Culture of Ancient Egypt,” by James Putnam; “The Rape of the Nile: Tomb Robbers, Tourists and Archaeologists in Egypt,” by Brian M. Fagan. The museum website, linked above in the article, is a great source to learn about the history of the museum itself, its initiatives and its collections.

The first modern gynecologist was an Italian woman

Talking about Trotula also means talking about the first School of Medicine conceived in a modern sense, that of Salerno. The Scuola Medica Salernitana was founded in the 9th century to bring together the medical knowledge inherited from the Graeco-Roman world and that coming from Arabic and Jewish sources. The Scuola Medica Salernitana reached its golden period in the 11th century, which is when Trotula studied and worked there.

Salerno is home to the first, properly organized medical school in history: well, this is already a pretty interesting and little known fact about Italy in its own right, but the figure of Trotula only adds more charme and wonder to it. First of all, because she is a pretty mysterious figure (but we know she existed!), then because she was a female practicing a very much masculine art, that of medicine. Thirdly, she specialized in something surrounded by taboo: gynecology and obstetrics. Trotula (also known as Trota, Trottula, Trocta, Troctula) came from the noble salernitan family of the De Ruggiero, and it was certainly her social status to permit her to study and later teach in the Scuola Medica Salernitana which was, let’s not forget it, a university. We know she was not the only woman practicing and teaching medicine at that time in Salerno, but she remains the best known: she’s considered the most famous of all the mulieres Salernitanae, the women of Salerno who were active in the development of medicine.

Trotula left, or so it’s believed, a series of treatises on gynecology, obstetrics and hygiene, which can be considered rightly the early foundations of each of these disciplines. De Passionibus Mulierum ante in et post Partum (on the problems of women before and after giving birth, also known as the “Trotula Major”), De Ornatu Mulierum (on cosmetics, also known as the “Trotula Minor”) and the Practica Secundum Trota are texts largely attributed to her, but the actual authorship of which is still debated by some.

Whether these texts were written by her or not, the historical relevance of Trotula and her research for the development of modern medicine are paramount. Not only an Italian, but a woman doctor in a period where women were very seldom allowed to learn more than cooking and sewing. Well done, Trotula, well done…

Learn more about it: “The Trotula: a Medieval Compendium of Women Medicine,” by Monica Hellen Green; “Medieval Writings on Secular Women,” by Patricia Skinner and Elisabeth M.C. Van Houts.

It was an Italian who taught the French the art of scents

where he exported the art of perfume making

(sir gawain/wikimedia)

The art of modern perfume making is tied to France: Grasse, in its beautiful southern regions, is the Mecca of quality essences and perfumes and all major perfumeries in the world have their formulas produced here.

But the French didn’t learn it all by themselves.

It was, in fact, an Italian to introduce the secrets of essences to the people of France. It was the 16th century, more precisely 1533, when Caterina de’ Medici, then 14, became wife of the future king of France, the Duke of Orléans (also 14) and moved to Paris. Paris was beautiful, but young Caterina was afraid of missing her Florence, so she brought along with her a little entourage, including her personal perfume maker, Renato Bianco.

Perfume making was common practice in Italy; its secrets and techniques were jealously guarded by monks and those of the monastery of Santa Maria Novella in Florence were particularly known for their expertise. Well, Renato Bianco grew up with them: he was abandoned at birth and, as many other babies at that time, he was left outside the doors of a monastery. Renato developed immediately a passion for chemistry, so learning about perfumes was a natural step. So well he learnt the arts of perfume at the Santa Maria Novella monastery, that he became the official perfume maker of the de’ Medici family.

When Caterina had to move to Paris to marry Henry II, future king of France, Bianco followed her and kept doing there what he knew best: creating scents. Soon, the passion for perfumes spread in the French capital and plenty of young people came to Bianco to learn this special, amazing art. Perfume shops opened up a bit everywhere in the city and René le Florentin (Renato the Florentine), as Bianco was lovingly known there, became a bona fide VIP. It was the beginning of France’s hegemony in the world of perfume creation and production.

And all thanks to an Italian orphan brought up in a monastery.

Learn more about it: “The Chemistry of Fragrances: from Perfumer to Consumer,” by Charles Sell; ” “Catherine de Medici: a Biography,” by Leonie Frieda; “Perfume,” by Patrick Suskind; “The Essence of Perfume,” by Roja Dove.

Julius Caesar was very ill

(Andrew Bossi/flickr)

Plutarch already spoke about Caesar‘s poor health in his Parallel Lives. According to the Greek historian, the great Roman commander suffered from epilepsy, but more recent studies carried out by Francesco Galassi and Hutan Ashrafian of the Imperial College of London, seem to bring to a different conclusion. The two researchers have analyzed sources, both Latin and Greek, on the last years of Julius Caesar’s life, as well as traced a sort of medical family history of the dictator, and reached the conclusion that, very likely, Caesar didn’t suffer from epilepsy, but was rather victim of a series of minor strokes, which would temporarily affect his mental and physical capabilities.

Some of the symptoms identified by Galassi and Ashrafian in the classical texts analyzed were vertigo, weakness of legs and arms, depression, migraines, severe mood swings and sudden falls. As recounted in a recent article appeared on the Italian history magazine “Focus Storia,” Caesar often showed these symptoms in public: once, he began trembling uncontrollably during a speech by Cicero; another time, he couldn’t stand from his seat in the Senate when the other Senators honored him. Both cases were interpreted by ancient historians as signs of, respectively, emotional involvement and defiance, but today’s research may point towards a different state of things.

Interestingly, some think Caesar may have suffered from a different type of genetic illness, Marfan Syndrome. The syndrome affects human connective tissues, and is usually not life threatening, unless it invests internal organs in which case it can become fatal. Usually, sufferers of Marfan’s tend to have longer limbs and fingers: Abraham Lincoln and Nicolò Paganini were said to have it and even great pharaoh Akhenaton is among the historical figures who may have suffered from the disease.

Learn more about it: “Parallel Lives,” by Plutarch; “Caesar: the Live of a Colossus,” by Adrian Goldsworthy; “Giulio Cesare soffrì di ictus ripetuti.”

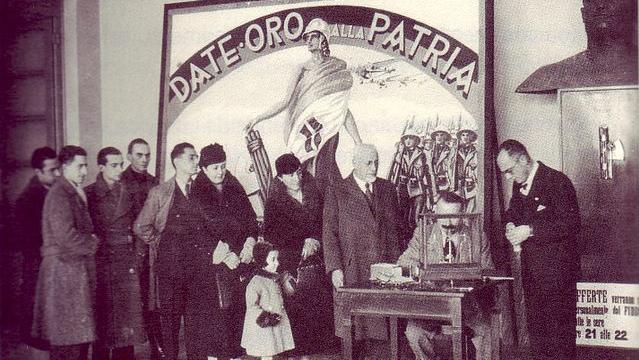

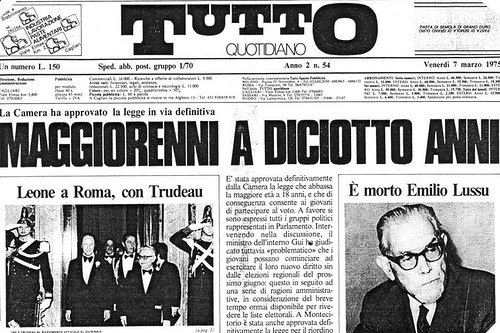

Autarchia e oro per la patria

In 1935, Fascism was enjoying its golden period in Italy and Mussolini felt more than ever the necessity to give to his country a colonial empire. The League of Nations (formed in 1919 after the end of First World War) was against an Italian military action in Africa and made it pretty clear to Mussolini, who decided to act nevertheless, especially after the situation deteriorated around Ual Ual. The 1935 invasion of Ethiopia was the beginning of a war that was to last about a year and would eventually end with the inclusion of the African land to the “Italian Empire,” albeit for a very short time (Ethiopia was conquered by the British in 1941).

Acting against the League of Nations, however, meant sanctions against Italy and the country had to make do on its own for a while. With a type of action typical of Fascist times, the government turned a bad situation into an opportunity to show the world Italy’s potential for greatness: you don’t want to help us? We’ll do it all on our own, and better! This could be a modern slogan for autarchia (autarchy, that is, being self sufficient economically, politically and juridically), the form of economical approach chosen by Italy (and Germany) during the Fascist era.

The idea of being entirely self sufficient presented a series of advantages for the régime’s propaganda machine: clearly enough, the image of Italy and its greatness could only be made more vivid by the fact the country was able to support itself without foreign interference (and by “without foreign interference” I mean the complete annullment of any type of commercial relation with foreign lands not part of Italy’s colonial territories) and for an amount of years Italians, energized by Mussolini’s verve and the fact things were going marginally better than before, kind of bought into that. It is in this context that the Oro per la Patria event took place: it was the 18th of November 1935 and Italians were asked to surrender their gold wedding bands and any other type of gold, to the state. The gold was to be converted into liquid money to make sure the country could survive on its own. Many Italians embraced the initiative fervently and gave up their gold wedding rings (for many, the sole gold object owned) and received an iron one in exchange.

Autarchy went on pretty much for the whole thirties and things only got worse with the war, when the real consequences of autarchy itself finally came into being: soon, it became clear it wasn’t only a matter of not having certain types of foods or materials, but rather of not being able to produce enough of whatever was needed to fight a war. Italy on its own, was not able to produce enough quality fabric to clothe its army, or had enough leather to give them strong boots. All was made within the country and with national materials, but to quicken production and make it less expensive quality was neglected.

Most of the men and boys who went fighting on the Russian front, for instance, had uniforms made with a hitchy synthetic fabric that couldn’t repair them from the cold: those among them who were lucky enough, managed to buy sheep skin coats in Romania, while still en route to Russia. The others suffered unspeakable cold throughout the Russian Winter months.

Learn more about it: “Mussolini’s Italy,” by R.J.B. Bosworth; “The Fascist Revolution,” by Marla Stone; “Legacy of Bitterness: Ethiopia and Fascist Italy,” by Roberto Scacchi.

As you can see, history is not all about dates and battle names: history gets into the thick and thin of culture and people’s lives and this is why it’s so fascinating and interesting to learn.

I don’t know if I convinced you to start a career as historians, but I hope this series of little known facts about the history of Italy tickled your curiousity to learn more about this beautiful country and the facts and people that made it.