Agriculture, tourism and the food industry are essential to Italy’s economic growth

I was born in the late 70s and, to my memory, there has not been a time when my country was not economically struggling: I have no recollection of the news mentioning anything different from “unemployment rise,” “economic crisis,” “higher-than-ever national debt.” History says the early to mid-eighties were not that bad, but I was too young to remember, so I am left with this idea: Italy, pretty much throughout my entire lifetime, has been a country in difficulty.

With this, I am not trying to say I lived a life of struggles, or that the majority of Italians did: I come from an average Italian family who owns a house, sent its two kids to college, worked hard and earned right. There were loads of families like that in Italy, when I was a kid, and there still are. But many less.

The truth is that Italy, a country which once had one of the six strongest economies in the world and still manages, in spite of everything, to remain among the first ten, struggles: the high amount of taxes to be paid hits particularly hard younger, independent workers or newly established firms, meaning younger generations have been finding it especially hard to get started and keep a business profitable.

Gloomy skies at the horizon, so. But an article published on La Stampa just about four weeks ago, made me feel a bit better about the future: in it, author Mario Deaglio simply explains how Italy has, indeed, the answers to its economic problems, it just needs to look at its land and its culture. Sounds like nothing new, you say? Well, you are right, but this time, it looks like Italians may just take this thing seriously…

Italy: the country of a million resources and little inventive

The post-war industrialization of the country brought wealth and comfort to Italians: those who came of age in the early ’60s, had a stable job by the age of 20, got married a couple of years later and would be on the property ladder before turning 30. For them, it was very unlikely to be forced to move to another town, let alone another part of Italy or country, to find a rightly paid, stable job, which they very likely maintained until now, retirement time.

Their children, who entered the job market in the early ’90s, already had to struggle: work commuting became much more common and often, even when living alone, they had to ask for their parents’ financial support here and there.

My generation – those in their mid thirties to early forties today – and their younger siblings entered the job market later and in the wrong moment.

Later, because a large majority of us went to university and in Italy university is ridiculous, in the sense you can go “fuori corso” (that is, not taking all your exams when you are supposed to and still manage not to be unceremoniously kicked out of the faculty for being lazy) and extend the time you need to graduate indefinitely. In the wrong moment, because after university, there were not many work opportunities around. Some of us emigrated abroad, others remained and, when lucky, found a (very likely, badly paid) job that dissatisfies them: mind, I am not maintaining all Italians are in a job they detest, but let us just say things are not peachy.

Analysing a successful past to create a prosperous future?

Italy could really consider itself out of the crisis if its economy could reach and keep an annual GDP growth of 2-2.5%. Should this happen and should – and this may not be that easy to achieve, Deaglio underlines – the country manage to keep public expenditures under control, Italy could lower its unemployment rates considerably and reach German levels within 10-15 years.

At least theoretically, then, Italy knows how to get out of the tunnel and return the prosperous country it once was: but what a struggle it will be: keeping public expenditures within limits means tackling seriously the endemic Italian issue of corruption and regional financial waste which, in my own humble opinion, is far from happening. And even if that was successfully done, how could the country reach that 2.5% of GDP growth and keep it going year after year?

In spite of being still relevant in the sectors, Italy has lost its supremacy in the IT (think Olivetti), pharmaceutical and chemical industries: that was the world of Italy’s prosperous 1970s and 1980s, a world which, experts say, no longer matches the country’s economical panorama.

Before being an industrial power, though, Italy was good at something else: agriculture. And it is, indeed, to agriculture – in all its declensions – that the country should look at to help the economy recover from the crisis. Think not, though, a full return to the bucolic lifestyle of pre-industrial Italy, but rather a highly specialized type of agriculture, entirely organic and practiced using old, well-established techniques, yet with all the ameliorations modern technology can bring.

may be the right way to help Italy’s struggling economy (Fabio Riva/Flickr)

Why would investing in organic, sustainable agriculture be the right path for Italy? Because Italy’s tradition and the modern market say so.

Italy is known for the quality of its produce, which is exported all over the world and creates a large part of the country’s income. The same, of course, has to be said about Italian traditional food products known, loved and sold everywhere in the world. Truth is that, in spite of the economic crisis, the brain drain and the rise in taxes, Italy’s agricultural and food sector remains strong and it is here, specialists say, the country needs to invest time and money to gained back its prosperity.

The future is green

The data presented by Deaglio in its article strengthens these considerations. Italy is world leader in the production and export of 77 agricultural and food products, for 23 of them, Italy is the largest producer in the world; for the other 54, the country is either at the second or third place. Some among them are expected: wine, pasta, salumi, tomatoes. Others may come more as a surprise: beans, cherries, vinegar, sardines.

The majority of the products exported (44.3%) comes from organic farms or businesses that only use organic produce to create their products: this is just a hair less than twice as much the amount of export demands for non-organic produce and products. Similar considerations can be made about the most innovative companies in the country: “green” businesses are twice as innovative as “non green” ones.

Reality, then, says that investing effort and funds in agriculture may be the right way to return to feel like a real economic power: more precisely, the country should invest in the “filiera alimentare,” that is, all sectors and businesses related to what we eat: from produce and products, to agriculture related scientific research and cooking books, all is part of it. The secret, it seems, is truly to look back at the country’s own tradition in producing, eating and living well and to apply modern knowledge and how-to to it.

Bring the green into your holidays

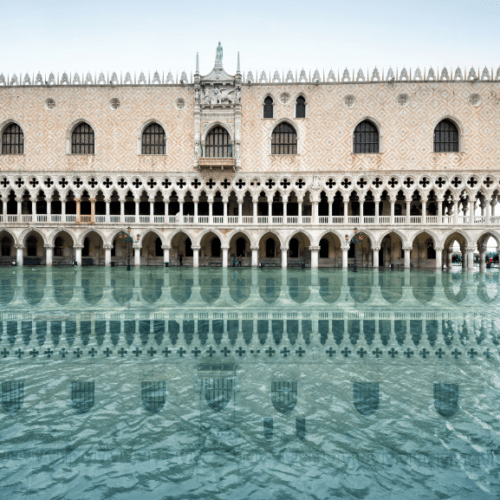

When thinking of Italy, two things immediately spring to mind: good food and art. And Sophia Loren, of course, but that is another story.

It is undeniable that many come to Italy every year to sightsee and to eat well. Data show that Italy is by far and large the most visited European country, and it goes without saying that our visitors are more often than not also attracted by the possibility to enjoy some amazing food between a museum and the other. From this evident truth, Deaglio concludes, Italy should start bulding up its economic future, investing right and, crucially, coordinating all agricultural and culinary-touristic sectors at national level.

Re-evaluation of the past through modernity, keeping it green, working at national level: following these rules, Deaglio (and data) says, should be a good start to bring Italy back on track economically: it may not solve all of our problems, but finally getting out of economic limbo could be a great place to start.

If you want to read Mario Deaglio’s interesting piece in full, you can find it here (mind, it’s in Italian!)

Francesca Bezzone